The HTTP part 1 - Let's start small

We all use it, you used it when you entered here - The HTTP Protocol. If you are a developer there is a high chance that you are dealing with HTTP. It is so easy to write a web app nowadays. If you code let’s say in Java, you can just slap some Spring Boot dependencies, @RestController here @GetMapping there and BOOM - you’ve got a working application that communicates through HTTP. But how does it work under the hood?

Why am I writing this?

I work as a developer in a team that provides integration with the infrastructure to our apps. I’ve debugged through HTTP Server quite a few times. I also deal with distributed systems that communicate through HTTP. However, I still feel that I don’t know that much about the internals of HTTP. And what is the better way to learn how HTTP works than to build server by myself?

The plan

The plan is NOT to a create production-grade “unconditionally compliant” RFC2616 HTTP server, because there are lots of them right now that have already proven to be great, like Tomcat or Undertow. I want to implement parts that interest me, especially communication. I could just read the RFC and study code of existing HTTP Servers, but the code is not that easy to understand and it’s more fun to build it ourselves and learn by mistakes. I also want to focus on things that can go wrong. If you know 8 fallacies of distributed computing you know that things will go wrong, so my idea is to test some scenarios on a simple server that we can understand.

The language

Probably the best idea would be to write it in C because it is as close to the kernel as it can get but eventually, I want to build abstractions on top of it, so I’ll go for higher level language. I mostly code on JVM, therefore the natural choice is Java, but I prefer Kotlin due to multiple reasons that were already discussed online. I hope that extra syntax won’t be a problem to understand the bigger picture. I also want to explore more low-level abstraction available in JDK, those are often very well hidden behind walls of frameworks.

The name

The codename is “Not A Production HTTP Implementation”, in short - NAPHI (with silent H!).

The basics

HTTP is a stateless protocol built on top of TCP/IP. When you are entering a website, your browser connects to a server and send a request like “please give me a website under some address” or “please save my privacy preferences”. The server then processes request and answers with a response like “here is HTML representation of website” or “OK, I updated your preferences”.

Currently, the newest version is HTTP/2.0, but at first we will implement parts of HTTP/1.1 because it’s much easier and well known. I hope we will eventually implement some parts of HTTP/2.0.

“Hello, World!” of HTTP

Let’s build a server that will respond with status code 200 (OK) and body of the legendary “Hello, World!” phrase.

package org.naphi

import org.slf4j.LoggerFactory

import java.io.PrintWriter

import java.net.ServerSocket

import java.net.Socket

import java.util.concurrent.Executors

import java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit

class Server(val port: Int): AutoCloseable {

private val logger = LoggerFactory.getLogger(Server::class.java)

private val serverSocket = ServerSocket(port) // start a socket that handles incoming connections (1)

private val threadPool = Executors.newSingleThreadExecutor()

init {

threadPool.submit { // (6)

try {

handleConnections()

} catch (e: Exception) {

logger.error("Problem while handling connections", e)

}

}

}

private fun handleConnections() {

while (!serverSocket.isClosed) {

serverSocket.accept().use { // (2)

try {

handleConnection(it)

} catch (e: Exception) {

logger.warn("Problem while handling connection", e)

}

} // (5)

}

}

private fun handleConnection(socket: Socket) {

// we should use a buffered reader, otherwise we will be reading byte by byte which is inefficient

val input = socket.getInputStream().bufferedReader()

val output = PrintWriter(socket.getOutputStream())

// let's read just one line now, if we try to read everything we would block

val requestLine = input.readLine() // (3)

logger.info("Received request: {}", requestLine)

output.print("""

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Hello, World!""".trimIndent()) // (4)

output.flush() // make sure we will send the response

}

override fun close() {

serverSocket.close()

threadPool.shutdown()

threadPool.awaitTermination(1, TimeUnit.SECONDS)

}

}

fun main(args: Array<String>) {

Server(port = 8090)

}

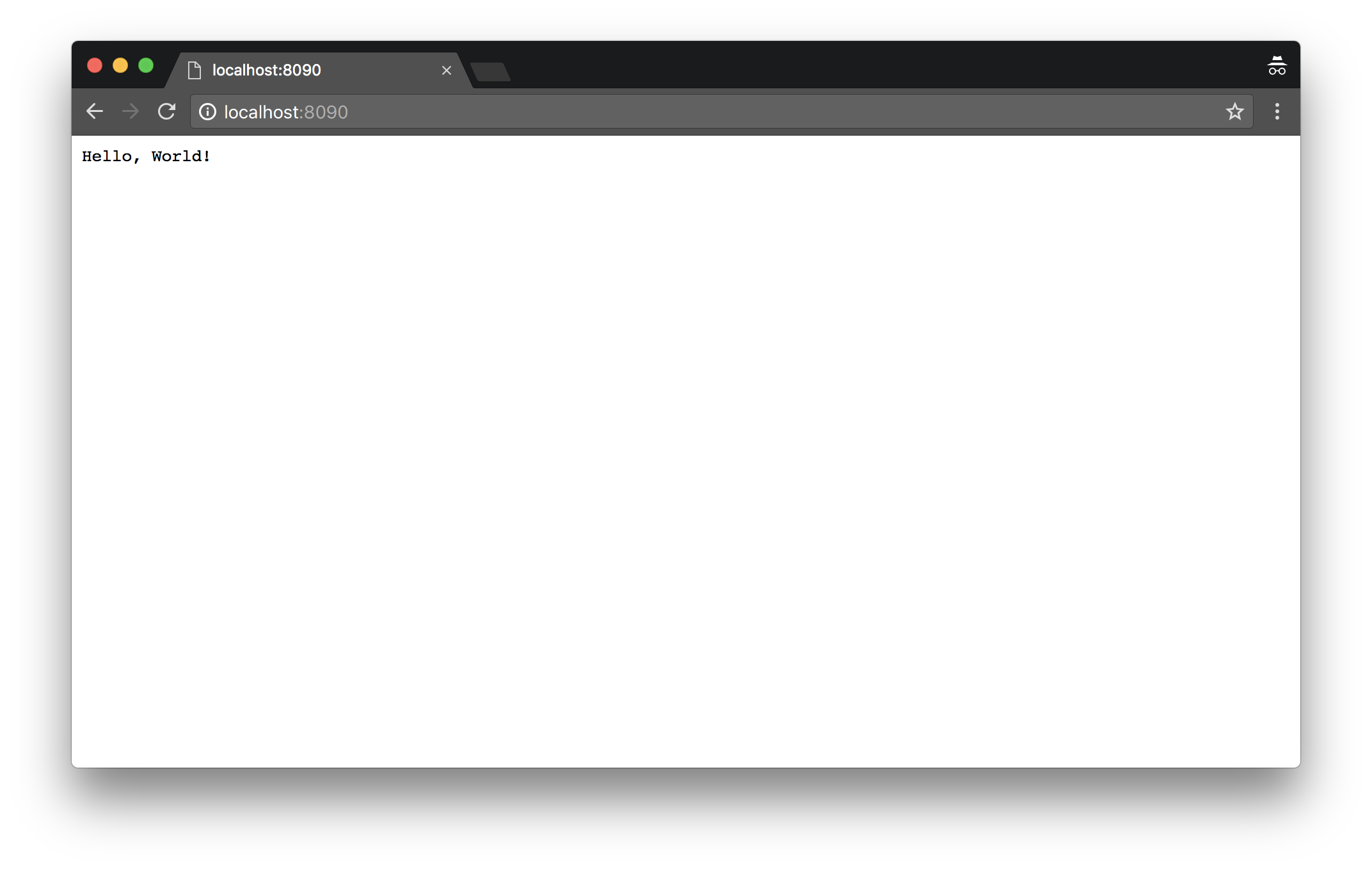

We can now go to http://localhost:8090 in our browser and there we go, we’ve got a website!

Let’s review that. Firstly, we created an instance of java.net.ServerSocket which created a socket to listen to incoming connections (1). Then after we received a connection (new socket) (2), we read a line from a buffered stream (3). After that, we printed to the output stream the response (4) and closed a socket (the use {} block is equivalent of Java’s try-with-resources) (5).

The Server is run on another thread (6), but it isn’t multithreaded itself. In my opinion, it’s easier to use from the user perspective, which I will show later.

Sadly, there is also a lot of try catching, we have to be careful.

We have to make sure that errors from handleConnection(Socket) are logged and ignored. Otherwise, error from single request could blow up the whole server - it would stop listening to other connections.

handleConnections() should also be wrapped in try-catch, because we are running it in ExecutorService. It will not log an exception by itself.

What is a Socket?

A Socket is an interface for receiving and sending data over a network. When we create a Socket, we actually create a file descriptor (FD). A file descriptor is a special handler for I/O operation on I/O resources like files or network. On Linux, we can check FD under the /proc/PID/fd/ path.

There are different kinds of sockets, HTTP is a protocol over TCP so we will be using SOCK_STREAM

To run a server we would:

- Create a socket with

socket()system call - Bind (assign) the socket to an address and port with

bind() - Mark socket to listen to incoming connections with

listen() - Accept incoming connections with

accept(). This would create a brand new socket (with new FD) for a new connection that was established - Send and receive data with

recvfrom(),sendto()

We can check if that’s true by using strace - a tool for monitoring app’s system calls

vagrant@vagrant-ubuntu-trusty-64:~$ jps

5616 jar # that's our process

5626 Jps

vagrant@vagrant-ubuntu-trusty-64:~$ sudo strace -e 'trace=socket,bind,listen,accept,sendto,recvfrom' -f -p 5616

Process 5616 attached with 10 threads

# server is starting

# that's the ServerSocket(port) part

[pid 5617] socket(PF_INET6, SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_IP) = 5

[pid 5617] socket(PF_INET6, SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_IP) = 6

[pid 5617] bind(6, {sa_family=AF_INET6, sin6_port=htons(8090), inet_pton(AF_INET6, "::", &sin6_addr), sin6_flowinfo=0, sin6_scope_id=0}, 28) = 0

[pid 5617] listen(6, 50) = 0

# connection is being made after curl localhost:8090

# that's the serverSocket.accept() and receiving/send msg part

[pid 5617] accept(6, {sa_family=AF_INET6, sin6_port=htons(41660), inet_pton(AF_INET6, "::ffff:127.0.0.1", &sin6_addr), sin6_flowinfo=0, sin6_scope_id=0}, [28]) = 7

[pid 5617] recvfrom(7, "GET / HTTP/1.1\r\nUser-Agent: curl"..., 8192, 0, NULL, NULL) = 78

[pid 5617] sendto(7, "HTTP/1.1 200 OK\n\nHello, World!", 30, 0, NULL, 0) = 30

It is a bit easier on the client side:

- Create socket with

socket() - Connect to server with

connect() - Send and receive data with

recvfrom()andsendto()

vagrant@vagrant-ubuntu-trusty-64:~$ sudo strace -e 'trace=socket,connect,sendto,recvfrom,close' curl http://localhost:8090

...

socket(PF_INET6, SOCK_DGRAM, IPPROTO_IP) = 3

close(3) = 0

socket(PF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP) = 3

connect(3, {sa_family=AF_INET, sin_port=htons(8090), sin_addr=inet_addr("127.0.0.1")}, 16) = -1 EINPROGRESS (Operation now in progress)

sendto(3, "GET / HTTP/1.1\r\nUser-Agent: curl"..., 78, MSG_NOSIGNAL, NULL, 0) = 78

recvfrom(3, "HTTP/1.1 200 OK\n\nHello, World!", 16384, 0, NULL, NULL) = 30

recvfrom(3, "", 16384, 0, NULL, NULL) = 0

close(3) = 0

The tests

Normally I would choose Groovy + Spock, but I don’t really like the integration with Kotlin code. I would like to use Kotlin Test, but I can’t stand that I cannot run a single test from IDE. I will stick to Kotlin + JUnit + AssertJ for now. I may replace it later.

To test our server, we have to use an HTTP Client. Usually, I would use a wrapper like RestTemplate or Retrofit, because of nicer API, but let just use bare bone HttpURLConnection from JDK. It’s a nice occasion to explore how it works.

class ServerTest {

@Test

fun `server should return OK hello world response`() {

// given

val server = Server(port = 8090)

// when

val connection = URL("http://localhost:8090/").openConnection() as HttpURLConnection

connection.connect()

val responseCode = connection.responseCode

val response = connection.inputStream.bufferedReader().readText()

connection.disconnect()

// then

assertThat(responseCode).isEqualTo(200)

assertThat(response).isEqualTo("Hello, World!")

// cleanup

server.close()

}

}

Thanks to the fact that our server is listening on connections on another thread, we can start it and immediately make a request. Otherwise, we would have to start it in executor service. This may not be a problem now, but we will save some code later with multiple tests.

What’s next?

We managed to build a simple HTTP server! The next step would be to look at our implementation and see what is going on when multiple connections are established.

Code samples

The code for this part is available on my Github.

Other articles of the series

This article is a part of the HTTP series